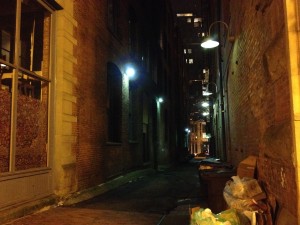

As long as I’m not driving, I love fog. Wandering somewhere I half know, only able to see a few feet in front of my face while mist renders the air nearly solid is exciting for me.

I want things to come out of the fog. I want to go into the mist and find secret islands.

But the thing about fog is I know it will be burn off. Sooner or later, I’ll see the shape of what I know is there. Eerie and damp as it can be, I know it will disappear.

I’m working on maintaining this confidence as I write.

New projects I start and finish without pausing to worry over whether or not I’ve written the right scene or chosen the right word. I still work with care and attention, but I’ve shed the stress that comes from obsessively worrying about whether or not I’m making the right choices.

But that doesn’t apply to the unfinished works sitting in a folder on my laptop.

There are a couple of books that really want to be done. Pieces I could claim got interrupted by deaths, illnesses, accidents, other people’s deadlines, but the truth is that the stories are still somewhere in the fog inside my brain. As long as I believe the fog will eventually burn off and I’ll figure out how the story really goes, I’m fine.

The disheartening part of finishing these stories is that I’m not always certain about parts to keep. Or if the structure is clear. Or if I’ve focused on the right characters.

I just know there’s something out there, in the fog, and, like Mulder, I want to believe that if I hang in there long enough, I’ll figure the whole thing out. Or at least enough to type to the end of the book and send it to my copy editor.

At my keyboard, all of this makes sense. I don’t need to explain it to my dog, who is there for most of my confusion, breathing the same essential oils I burn to motivate, nudge and clarify. Dog is my co-writer. He types nothing, but having him in the room is an essential part of my process. He’s there by my side as we metaphorical travel the fog together. Essential. Silent, except for his farts.

At my keyboard, all of this makes sense. I don’t need to explain it to my dog, who is there for most of my confusion, breathing the same essential oils I burn to motivate, nudge and clarify. Dog is my co-writer. He types nothing, but having him in the room is an essential part of my process. He’s there by my side as we metaphorical travel the fog together. Essential. Silent, except for his farts.

Explaining this to friends who want to know what’s going on with me is harder. The ones who don’t write hone in on my disorientation and worry or merely end up confused by my inability to narrow my mess-in-progress to a pithy pitch line. I write fiction without an outline. It just works better for me, but it leaves little to say to other people. Mermaid, blah, blah. Steampunk, blah, blah. My central character is giving me troubles because she might not be the right central character, blah, blah.

And then I’m driving home, realizing that my friend is concerned for my mental state. I haven’t done a good job of explaining that this lost, uncomfortable, occasionally boring bit is an integral part of the process—that, yes, I really do like spending my life in a muddle a good part of the time.

Other writers get this. We swill tea or alcohol and spout half sentences at each other and despite the lack of clear conversational structure, a kind of communication happens.

It’s comforting really. Not quite the clear communication my dog achieves through sniffing other dogs, but close. And, fortunately, since writers are for the most part human, not as physically intimate.